|

SG TRUST

SG EVENTS

SG INFO

ASSIGNMENTS

COACH EXPERIENCE

TEST SPOTS

NEW ROUTE

JAP OCCUPATION

ESPLANADE

CHINATOWN

CONFUCIOUS

LITTLE INDIA

INDIAN

INDIAN HERITAGE

KAMPONG GLAM

MALAYS

CIVIC DISTRICT

FULLERTON

SINGAPORE RIVER

HDB

HDB over the years

URA

URA MODEL

HISTORY

SG LKY

SG PIONEERS

SANSUI

DEVELOPMENT

MERLION

FORT CANNING

ORCHARD ROAD

CHINESE

PERANAKAN

CHURCHES

ARMENIA

GREENING SINGAPORE

WATER &

RESERVIORS

PARKS

BOT GDN

NATURE

MARINA BAY

GARDENS

MARINA BAY

DESTINATIONS

SG MONUMENTS

MANDAI

SG SENTOSA

SG CHANGI

SG TOURISM

SG TOURS

SKILLS

TG68 LESSONS

ROAD NAMES

TOUR MANAGEMENT

SG TOURS

RACIAL HARMONY

YYW

MERLION

SGTG6688

THIEN HOCK KENG

BUDDHA TEETH

HAWKER CULTURE

SG TOURS VIDEOS

FOOD

TRANSPORT

CBD & REGIONAL TOWNS

GREETINGS

MALAYSIA

JOHOR AND JB

KULAU LUMPUR

PENANG

TIOMAN

SG FENG SHUI

SG PAINTINGS

SG MODERN JUDAISM & JEWS

SG TICKETS

| |

ESPLANADE

|

PADANG |

|

|

|

| |

LITTLE

RED

DOT

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

.jpg)  .jpg)

●

●

承前启后的新月:艺术作品。從洞里往前看和向后看是不同建筑,新和旧的对比。新的是金沙,旧的是市政区。

团队管理 走去大草坪,从左往右讲解

|

一长条走道叫海滨公园,以前叫伊丽莎白道。

这块地是填海的。

为 纪 念 英 国

⼥

皇 伊 丽 莎

⽩

⼆

世 的 加 冕。

是早期的沙爹俱樂部所在地。

|

|

.jpg)

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

Lim Bo Seng -Singapore’s indefatigable war hero

|

|

Background

of Lim

Bo

Seng

Lim Bo Seng’s life

story reflects

his unwavering

patriotism and

resilience. Born

in Fujian,

China, Lim moved to Singapore at 16 and attended Raffles

Institution, where he was a classmate of Yusof

Ishak, Singapore’s first president.161

He later

dropped out

of the

University of Hong

Kong to take over his

family’s businesses,

including a biscuit and brick manufacturing company.162

A successful merchant, he held prominent positions in several

organizations, such as the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce and

Industry and the Singapore Hokkien Association.163

A father of eight, Lim also organized fundraisers and protests in the

1930s to support anti-Japanese efforts.164

When Japanese forces invaded Malaya in December 1941, Lim was appointed

head of labour services for

the Overseas

Chinese Mobilisation

Council.165

He gathered

10,000 men

to construct defences

and destroy the Causeway to impede the Japanese advance. As Singapore

fell, Lim made the difficult decision to leave the island, escaping by

sampan to India while his family stayed behind for safety.166

In India, he joined Force 136, a British-led resistance network,

recruiting Chinese agents to gather intelligence.167

However, betrayals within the group led to the arrests of many members,

including Lim, who was captured while working with the British to expand

the intelligence network in Malaya.168

In captivity at Batu Gajah Gaol, Lim was starved, tortured, and

ultimately succumbed to malnutrition, dysentery, and mistreatment at the

age of 35.169

Despite his suffering, he shared his

rations with fellow

prisoners and

remained steadfast, refusing to

divulge information

to the Japanese.170

After the war, his remains were repatriated to Singapore and buried with

full military honours at MacRitchie Reservoir.171

His wife, Gan Choo

Neo, managed to protect their

family by moving between

hideouts, including St.

John’s Island.172

Lim’s legacy as a patriot and war hero endures, symbolised by the

memorial that bears his name.

Funeral Service

for Lim

Bo

Seng

On the 13th of January 1946, the steps of the Municipal

Building would host the funeral ceremony of the late Major-General Lim

Bo Seng.64

Having suffered at the hands of the Japanese military police in Perak,

where he was held at Batu Gajah Gaol, Lim succumbed to malnutrition,

dysentery, and torture at the age of 35 in 1944, reportedly having been

“reduced to a bag of bones”.65

His remains were initially buried

in a mass grave near prison grounds, but in

December 1945

his widow

Gan Choo

Neo travelled

up to retrieve her

husband’s remains. Lim was thus

exhumed and returned to Singapore for reburial at Macritchie Reservoir.66

Lim

Bo Seng Memorial

The Lim

Bo Seng

Memorial honours the

bravery and sacrifice of war hero

Lim Bo

Seng, a

key

figure in Singapore’s World War II history. In 1946, a committee was

formed in response to a promise

made by

British authorities at Lim’s

funeral at

MacRitchie – to

support the

construction of a memorial to the late war hero.153

Colonel Chuang Hui Chuan would take up chairmanship of the newly established Lim Bo Seng Memorial Committee, whose

task was to fundraise and work with the colonial government to turn the

proposed memorial into reality.154

Chuang Hui Chuan had previously worked alongside Lim in fundraising and anti-Japanese activities, and had served

as the

deputy head

of the secretive

Force 136

during the

war.155

Initial proposals to build a memorial

at the grave’s location in MacRitchie were rejected by the British for

reasons of size and inclusivity – what would have been a grand Chinese

memorial with features that enabled mourners to

offer incense and

perform Chinese mourning

rituals would look markedly

different when the memorial was eventually built.156

The British eventually accepted the committee’s sixth proposal, by which

time the committee was publicly frustrated with the process of working

with the British government. The memorial would be given a space in

Esplanade Park, and would be significantly reduced in size and features.157

This new memorial to Lim could be directly compared to the grander

Cenotaph a stone’s throw away – an attempt by the colonial powers to

retain control over war narratives and memoryscapes, to ensure that

local narratives would not trump the existing hold that the British

had on the

colony.158

Ng Keng

Sian, Singapore’s

first overseas-trained

architect, designed the memorial that was ultimately accepted and realized.159

He would blend traditional Chinese motifs with modern materials, drawing

from Chinese nationalist architecture in the monuments’ bronze roof and

four lion statuettes.160 |

Lim Bo Seng, the first son of contractor Lim Loh, was

born in a 99-room family housing complex in Fujian’s Nan’an County in

China. He left for Singapore at 16 and studied at the prestigious

Raffles Institution where he was classmates with individuals such as

Yusof Ishak, the future president of Singapore.

In 1929, Lim cut short his studies at the University of Hong Kong to

take over his father’s businesses, one of which was a well-known

construction company involved in the erection of major landmarks such as

Goodwood Park Hotel, Victoria Memorial Hall and Old Parliament

House.Lim’s business acumen put him in good stead to manage and grow his

father’s businesses. As a result he also became a prominent merchant. On

top of this, Lim served in key positions in a number of associations

such as the Singapore Contractors Association, the Singapore Chinese

Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the Singapore Hokkien Association.

Lim married teacher Gan Choo Neo

in 1930.She bore him eight children, one of whom died at a young

age. He was a loving father, taking his children to High Street on

weekends to read and buy books at Ensign Bookshop before adjourning to

Polar Cafe for cake and ice cream.

When war broke out in China, Lim stepped forward and took on an active

role in resisting Japanese advances, earning himself a distinguished

place in history as one of Malaya’s foremost war heroes. But his

anti-war efforts required great sacrifice. When Singapore fell to the

Japanese, Lim found himself having little choice but to separate from

his beloved family.

Clandestine missions

Lim’s anti-war efforts, where he organised fundraisers and protests,

began in the 1930s, before the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese war.

In December 1941, Japanese troops infiltrated Kota Bharu in Malaya in an

amphibious attack. Alarmed, the British called on Lim to help bolster

Singapore’s defence infrastructure. As head of Labour Services of the

Overseas Chinese Mobilisation Council, he gathered 10,000 men to erect

defences, run key services for the population, and blow up the Causeway

— a means in which the Japanese could storm Singapore.

With the Japanese on Singapore’s doorstep, arrangements were made for

Lim and his family to leave for their safety. However, with the Japanese

sinking evacuating vessels, Lim made the call to have them stay on in

Singapore, choosing instead to leave their side.

In a diary entry dated 11 February 1942, just days before the fall of

Singapore, Lim wrote that the decision to separate pained him greatly.

“To leave the dear Mrs behind at the mercy of the enemy would go very

hard against my own conscience. On the other hand, to remain with the

family in the event of enemy occupation, would not in any way improve

the situation but my presence may even make their lot very much harder.”

He added that his children were "too stupefied to realise what was

happening” as they kissed him goodbye. “I shall never forget the

tear-stained faces as long as I live. If there is anything I could do to

make up for what they were then going through, I shall not spare myself

to carry it out.” It was the last time he would see them. .

Lim left soon after by sampan, observing in his diary that the sky was

lit up by enemy fire in three directions — Pasir Panjang, Serangoon and

Bukit Timah. By morning, Singapore was “enveloped in a pall of smoke”.

Lim eventually found his way to India, joining Force 136, a secret

service unit established by the British and Chinese governments to

recapture Singapore.He was responsible for recruiting Chinese espionage

agents who could blend in with locals to gather intelligence.

Upon completion of their training, teams from Force 136 boarded a Dutch

submarine from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to re-enter the Japanese

controlled territory of Malaya. Lim was among them. While in Malaya,

Force 136 attempted to collaborate with the area’s main resistance

movement, the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army. It also set up a

covert network to gather intelligence.

Later, following some blunders and a betrayal, information was divulged

to the Japanese which led to the arrests of Force 136 agents. Lim, who

had left the group’s Bukit Bidor camp to raise funds and expand its

intelligence network, was also arrested.

Lim was mercilessly starved and tortured for information by Japanese

military police at the Batu Gajah Gaol where he was incarcerated. They

failed to break him. Despite his own plight, Lim shared his meagre food

rations with fellow prisoners. Compatriots who witnessed his last days

in prison said he had been "reduced to a bag of bones".He eventually

died of malnutrition, dysentery and torture at 35. Wrapped in a tattered

blanket, he was taken away in a wooden cart and buried in a mass grave

near the prison grounds.

A hero’s return

In Singapore, the Japanese who were baying for blood, were successful in

hunting down and killing eight of Lim’s relatives living at 855

Serangoon Road — a compound comprising three houses built by Lim Loh.

Lim’s wife, however, managed to outwit them, moving her family from one

hideout to another. At one point, she even sought refuge at St John’s

Island.

Following his unceremonious burial in Batu Gajah, Lim’s remains were

brought back to Singapore.After a funeral at City Hall, he was laid to

rest with full military honours on a hill overlooking MacRitchie

Reservoir where he used to court his wife. He was posthumously awarded

the rank of major-general by the Chinese Nationalist government in 1946.

Lim Bo Deng funeral

Lim Bo Seng's wife Gan Choo Neo on the far right in black during his

funeral service at Macritchie Reservoir. (Image from the Tham Sien Yen

Collection courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore)

On the 10th anniversary of his death, a memorial built in his honour was

unveiled at Esplanade Park. It is the only World War II memorial in

Singapore dedicated to an individual. It was gazetted a national

monument in 2010 alongside two other structures in the park.

In 2016, Lim’s personal diary which he left behind for his heartbroken

wife, resurfaced. One entry reads:

“You must not grieve for me. On the

other hand, you should take pride in my sacrifice and devote yourself to

the upbringing of the children. Tell them what happened to me and direct

them along my footsteps.”

|

林谋盛是承包商林禄的长子,出生在中国福建南安县一个有 99 个房间的家庭住宅区。16

岁时,他离开家乡前往新加坡,就读于著名的莱佛士书院,在那里,他与新加坡未来的总统尤索夫·伊萨克等人是同学。

1929

年,林谋盛中断了在香港大学的学业,接管了父亲的企业,其中一家是著名的建筑公司,参与建造了良木园酒店、维多利亚纪念堂和旧国会大厦等主要地标建筑。林谋盛的商业头脑使他能够很好地管理和发展父亲的企业。因此,他也成为了一位杰出的商人。除此之外,林谋盛还在新加坡承包商协会、新加坡中华工商会和新加坡福建会馆等多个协会担任重要职务。

林谋盛于 1930 年与老师 Gan Choo Neo

结婚。她为他生了八个孩子,其中一个孩子在很小的时候就去世了。他是一位慈爱的父亲,周末会带孩子们去 High Street 读书,在 Ensign

书店买书,然后去 Polar Cafe 吃蛋糕和冰淇淋。

当中国爆发战争时,林有福挺身而出,积极抵抗日本的进攻,作为马来亚最重要的战争英雄之一,在历史上赢得了显赫的地位。但他的反战努力需要做出巨大的牺牲。当新加坡沦陷于日本人手中时,林有福发现自己别无选择,只能与他心爱的家人分开。

秘密任务

林有福的反战工作始于 1930 年代,即第二次中日战争爆发之前,他组织了筹款和抗议活动。

1941 年 12

月,日军发动两栖攻击,潜入马来亚的哥打巴鲁。英国人惊慌失措,要求林有福帮助加强新加坡的国防基础设施。作为海外华人动员委员会劳工服务负责人,他召集了

10,000 名士兵建立防御工事,为民众提供关键服务,并炸毁了堤道——这是日本人袭击新加坡的手段。

随着日本人来到新加坡门口,林有福和他的家人为了安全而安排离开。然而,随着日本人击沉撤离船只,林有福决定让他们留在新加坡,而不是选择离开他们。

在 1942 年 2 月 11

日的日记中,就在新加坡沦陷前几天,林有福写道,分开的决定让他非常痛苦。“把亲爱的夫人留在敌人的摆布下,这非常违背我的良心。另一方面,在敌人占领的情况下留在家人身边,不会以任何方式改善情况,但我的存在甚至可能使他们的命运更加艰难。”

他补充说,他的孩子们在吻别时“惊呆了,没有意识到发生了什么”。

“只要我还活着,我永远不会忘记那些泪流满面的脸。如果我能做任何事情来弥补他们当时所经历的一切,我会不惜一切代价去做。”这是他最后一次见到他们。

林宝龙乘舢板离开后不久,他在日记中写道,天空被三个方向的敌军火力照亮——巴西班让、实龙岗和武吉知马。 到了早晨,新加坡“被烟雾笼罩”。

林宝龙最终找到了去印度的路,加入了由英国和中国政府为夺回新加坡而建立的秘密服务部队 136 部队。 他负责招募能够混入当地人收集情报的中国间谍。

完成训练后,136 部队的团队从锡兰(现斯里兰卡)登上一艘荷兰潜艇,重新进入日本控制的马来亚领土。林宝龙是其中的一员。在马来亚期间,136

部队试图与该地区的主要抵抗运动——马来亚人民抗日军合作。它还建立了一个秘密网络来收集情报。

后来,在跟踪一些由于失误和背叛,情报被泄露给日本人,导致 136

部队特工被捕。林某离开该组织在武吉美罗的营地,筹集资金并扩大情报网络,也被捕了。

林某在被关押的华都牙也监狱被日本宪兵无情地饿死并折磨,以获取情报。他们没能打败他。尽管林某自己处境艰难,但他还是与其他囚犯分享了微薄的食物配给。目睹他在监狱最后几天的同胞说,他“瘦得只剩一副骨头”。他最终在

35 岁时死于营养不良、痢疾和酷刑。他被裹在破烂的毯子里,用木车运走,埋在监狱附近的一个集体坟墓里。

英雄归来

在新加坡,嗜血的日本人成功追捕并杀害了林谋盛的八名亲属,他们住在实龙岗路 855

号——一座由林乐建造的由三栋房子组成的建筑群。然而,林谋盛的妻子设法战胜了他们,将家人从一个藏身处转移到另一个藏身处。有一次,她甚至在圣约翰岛寻求庇护。

在华都牙也草草埋葬林谋盛后,他的遗体被运回新加坡。在市政厅举行葬礼后,他以军人礼仪安葬在俯瞰麦里芝蓄水池的一座小山上,他曾在那里追求妻子。1946

年,中国国民政府追授他少将军衔。

林谋盛葬礼

在麦里芝蓄水池举行的葬礼上,林谋盛的妻子颜珠娘身着黑衣,位于最右边。 (图片来自新加坡国家档案馆提供的谭先燕收藏)

在他逝世十周年之际,滨海公园为他修建的纪念碑揭幕。这是新加坡唯一一座以个人名义修建的二战纪念碑。2010

年,它与公园内的其他两座建筑一起被列为国家纪念碑。

2016

年,林先生留给心碎妻子的私人日记再次浮出水面。其中一条日记写道:“你一定不要为我悲伤。另一方面,你应该为我的牺牲感到自豪,并致力于抚养孩子。告诉他们发生在我身上的事情,并引导他们追随我的脚步。”

|

|

Situated at

Esplanade Park along

Connaught Drive, the

Cenotaph stands

as Singapore’s only war memorial

dedicated to honouring those who

sacrificed their lives

during the two world wars.189

It was unveiled on 31 March 1922 by the Prince of Wales, who later

became the Duke of Windsor and King Edward VIII.190

The Cenotaph is constructed from local granite and rises nearly 18

meters high; Bronze tablets inscribed with the names of World War I

casualties adorn the memorial.191

The five original steps

leading to

the structure are etched

with the

years of

the war: 1914,

1915, 1916, 1917,

and 1918.192

At the

pinnacle lies

a sarcophagus, adorned

with bronze

lion-head handles, symbolizing

courage, below it, a laurel wreath enclosing a crown represents victory

and the British Crown Colony.193

The front

of the

memorial bears

the inscription “The Glorious

Dead,”

accompanied by the

years 1914 to 1918.194

On the reverse side, a solemn tribute to World War II soldiers reads: “They

died that we might live,” inscribed in English, Malay,

Chinese, and Tamil.195

While no individual names are listed for World War II casualties, the

extended steps added in 1951 display the years

1939 through

1943.

The

remaining war

years, 1944

and 1945,

are engraved

at the base of the monument.196

History

The Cenotaph was initially constructed as

a tribute to the 124 men from

Singapore who perished in action during World War I.197

Designed by architect Denis Santry of Swan & Maclaren,

it was

inspired by

the Whitehall Cenotaph

in London.198

The foundation stone was laid on 15

November 1920 by Sir Laurence Nunns Guillemard, then Governor of the

Straits Settlements.199

The ceremony was attended by notable figures, including M. Georges

Clemenceau, the

then French

Premier, and

Major-General Sir

D. H.

Ridout,

who commanded the

Straits Settlements troops.200

The

memorial’s unveiling

took place

on 31 March

1922, led

by the

Prince of

Wales during

his tour of Malaya, India, Australia, and New Zealand.201

Among his

entourage was Lord Louis

Mountbatten, who would later return to Singapore after World War

II as the Supreme Commander of Southeast Asia to oversee Japan’s

surrender.202

Between 1922

and 1941,

annual memorial

services, including religious ceremonies

and military

processions, were held at the Cenotaph to honour fallen World War I

soldiers.203

These events ceased during the Japanese Occupation but resumed after

1945, with World War II casualties also being commemorated.204 Between 1922

and 1941,

annual memorial

services, including religious ceremonies

and military

processions, were held at the Cenotaph to honour fallen World War I

soldiers.203

These events ceased during the Japanese Occupation but resumed after

1945, with World War II casualties also being commemorated.204

In 1950, the government approved an extension to the Cenotaph’s base to

honour those who died in World War II.205

This addition, completed in 1951, marked an evolution in its role as a

remembrance site.206

By 1963,

Remembrance Day

services were

held at

both the

Cenotaph and the

Kranji War Cemetery (now the Kranji War Memorial).207

Today, Remembrance Day in

Singapore is primarily observed at the Kranji War Memorial.208 |

|

The

Cenotaph -They

died that we might live

The

Cenotaph, located at Esplanade Park along Connaught Drive, is the only

war memorial in Singapore that commemorates the sacrifice of individuals

who died in the two world wars. It was first unveiled on 31 March 1922

by the Prince of Wales (later Duke of Windsor and King Edward VIII).2The

war memorial was gazetted as a national monument on 28 December 2010,

together with two other structures at Esplanade Park – the Lim Bo Seng

Memorial and Tan Kim Seng Fountain.

History

The Cenotaph was first erected as a memorial in honour of the 124 men

from Singapore who died in action during World War I.

It was designed by

architect Denis Santry of Swan & Maclaren, and modelled after the

Whitehall Cenotaph in London, England.

The foundation stone was laid on 15 November 1920 by Sir Laurence Nunns

Guillemard, then governor of the Straits Settlements, in the presence of

M. Georges Clemenceau, then premier of France, and Major-General Sir D.

H. Ridout, the general officer commanding the troops of the Straits

Settlements.

The memorial was unveiled on 31 March 1922 in a ceremony by

the Prince of Wales during his tour of Malaya, India, Australia and New Zealand.Lord Louis Mountbatten, who was part of his entourage as

aide-de-camp, would return to Singapore after the end of World War II as

Supreme Commander of Southeast Asia to accept the Japanese surrender.

From 1922 to 1941, annual religious ceremonies and military processions

were held at the Cenotaph as part of memorial services to remember the

fallen soldiers of both world wars. Armistice Day on 11 November was

commemorated for World War I soldiers until 1941, before the Japanese

Occupation, when the memorial services ceased.

Memorial services resumed after 1945, and the fallen soldiers of World

War II are remembered as well. Since 1946, this commemoration has been

known as

Remembrance Day.

In 1950, the government approved an extension to the base of the

structure to commemorate those who died during World War II.The

extension was completed in 1951.

In 1963, the Remembrance Day service was held simultaneously at the

Cenotaph and Kranji war graves cemetery (Kranji War Memorial today).

In

Singapore, Remembrance Day continues to be commemorated at the Kranji

War Memorial.

The ANZAC Day has also been commemorated at the Cenotaph.

Description

The Cenotaph is made of local granite and

nearly

18 m high.

Bronze tablets on the memorial bear the names of the individuals who

perished in World War I. Each of the original five steps leading up to

the monument bears the war years, 1914, 1915, 1916, 1917 and 1918.

The

Glorious Dead-WW1

Crowning

the structure is a

sarcophagus with bronze lion’s head handles.

Below it is a bronze medallion consisting of a laurel wreath of victory

enclosing a crown, to which the soldiers had rallied. The crown is also

a symbol of the crown colony. Lower down is the inscription “The

Glorious Dead”, and below the inscription are the years 1914 to 1918.

They

died that we might live WW2

On the reverse side, though no names are listed to commemorate the World

War II casualties, the phrase “They died that we might live” is

inscribed in the four official languages: English, Malay, Chinese and

Tamil. The extended steps added in 1951 bear the war years 1939 to 1943

in succession, leaving the remaining years of the war, 1944 and 1945, to

be inscribed on the base of the monument.

There are 14 pylons on both sides of the stone structure showing the

names of famous World War I battles, with each battle surmounted by a

laurel wreath.

The Cenotaph is a simple, stately structure, wrought with just a hammer

and chisel.

|

纪念碑

纪念碑位于康诺特道沿线的滨海公园,是新加坡唯一一座纪念两次世界大战中牺牲者的战争纪念碑。它于 1922 年 3 月 31

日由威尔士亲王(后来成为温莎公爵和爱德华八世国王)首次揭幕。2 战争纪念碑于 2010 年 12 月 28

日与滨海公园的另外两座建筑——林谋盛纪念碑和陈金声喷泉一起被列为国家纪念碑。

历史

纪念碑最初是为了纪念第一次世界大战期间在战斗中牺牲的 124 名新加坡士兵而建造的。它由 Swan & Maclaren 的建筑师 Denis

Santry 设计,仿照英国伦敦的白厅纪念碑建造。

1920 年 11 月 15 日,时任海峡殖民地总督的劳伦斯·努恩斯·吉尔玛爵士在法国总理乔治·克列孟梭和海峡殖民地部队指挥官少将 D. H.

里杜特爵士的见证下,为纪念碑奠基。1922 年 3 月 31

日,威尔士亲王在访问马来亚、印度、澳大利亚和新西兰期间,为纪念碑揭幕。路易斯·蒙巴顿勋爵是威尔士亲王的随行人员之一,二战结束后,他以东南亚最高指挥官的身份返回新加坡接受日本投降。

从 1922 年到 1941 年,纪念碑前每年都会举行宗教仪式和军事游行,作为纪念两次世界大战中阵亡士兵的纪念仪式的一部分。 11 月 11

日的休战纪念日是纪念第一次世界大战士兵的日子,直到 1941 年日本占领新加坡之前,纪念仪式才停止。

纪念仪式在 1945 年后恢复,同时也纪念二战阵亡士兵。自 1946 年以来,这一纪念日被称为纪念日。

1950 年,政府批准扩建纪念碑底座,以纪念二战期间阵亡的士兵。扩建工程于 1951 年完工。

1963 年,纪念日仪式在纪念碑和克兰芝战争公墓(今天的克兰芝战争纪念碑)同时举行。在新加坡,纪念日继续在克兰芝战争纪念碑举行。

纪念碑还纪念澳新军团日。

描述

纪念碑由当地花岗岩制成,高近 18 米。纪念碑上的铜牌上刻有第一次世界大战中牺牲者的名字。纪念碑上原有的五级台阶上都刻有战争年份,即

1914、1915、1916、1917 和 1918。

光荣牺牲者 - 第一次世界大战

纪念碑顶部是一个石棺,石棺上有青铜狮头把手。石棺下方是一枚青铜奖章,上面是胜利的月桂花环,里面有一顶王冠,士兵们都为之团结起来。王冠也是英国直辖殖民地的象征。下方是铭文“光荣的牺牲者”,铭文下方是

1914 年至 1918 年。

他们牺牲是为了让我们在二战中活下去

在背面,虽然没有列出名字来纪念二战伤亡者,但“他们牺牲是为了让我们活下去”这句话用四种官方语言刻着:英语、马来语、中文和泰米尔语。1951

年增加的延长台阶依次刻有战争年份 1939 年至 1943 年,而战争的其余年份,即 1944 年和 1945 年,则刻在纪念碑的底座上。

石质结构的两侧有 14 个塔架,上面刻有著名的第一次世界大战战役的名称,每个战役上方都有桂冠。

纪念碑是一个简单的庄严结构,仅用锤子和凿子打造而成。 |

The

Civilian War memorial is the first memorial dedicated to

commemorating the civilian victims of the Japanese Occupation in

Singapore.209

Occupying a prominent location in downtown

Singapore, the

War memorial

represents the

collective suffering experienced

by the various

ethnic groups

in Singapore.210

Unveiled

on the

25th anniversary of

the Fall

of Singapore, the

construction project was spearheaded by the Singapore Chinese

Chamber of Commerce as

part of an

undertaking to exhume

and rebury

the remains

of Sook

Ching victims

uncovered in construction projects across Singapore.211

Architecture

The monument itself is made up of four white columns 67 metres in

height, tapering to a central point.212

These four columns would

symbolise the unity of Singapore’s cultures and races – they would

also give rise to the memorial’s colloquial nickname, the

“chopsticks”, as they resembled

two pairs of

tapering chopsticks.213

Buried beneath

the monument, in a

cavern or burial chamber, are 606 urns containing the cremated human

remains of victims, retrieved from

mass graves

uncovered in

Siglap and

Changi.214

These remains

would belong

to thousands of

unidentified

civilians previously buried

unceremoniously by the

Japanese

occupiers.215

In the centre of

the monument, between the four columns, is a large bronze urn

adorned by lion heads, serving as a symbol of the urns and remains

buried underneath.216

Initial proposals envisioned the monument resembling earlier memorials

constructed in Penang, Malacca, and Johor Bahru between 1947 and

1948.217

These monuments typically featured a single pillar inscribed with

Chinese dedications to the deceased.218

However, the design process unfolded during a pivotal moment for the

nation, just months after its separation from Malaya. With

nation-building at the forefront, the government and the SCCCI

committee deliberated

on the

monument’s significance;

rather

than solely

commemorating the suffering of the Chinese community, they sought a design that

symbolized a unified national identity.219

As a result, the single pillar evolved into four, transforming the

Civilian War Memorial into a testament to

shared suffering and

collective memory of the Japanese

Occupation.220

Planning and

Construction

Singapore would experience

rapid growth amidst modernizing projects in

the 1950s and 1960s,

as the nation sought to achieve decolonialisation and independence for

itself.221

As an unintended result of the

many residential and industrial construction projects carried out

throughout the island, mass graves were discovered in Siglap by accident

in February 1962.222

The area in Siglap off Jalan Puat Poon came to be known as the “Valley

of death”.223

The Singapore Chinese

Chamber of

Commerce and

Industry would

convene a

committee to

uncover more mass graves.224

Relying on information obtained from the public, including war survivors

and witnesses, the committee would eventually uncover and

exhume 2 more mass graves on

Changi Road and 40 more mass graves in Siglap.225

The

discovery and

exhumation of

these remains

would be

the beginning

of a

healing process

for the Chinese community, who were anxious that the spirits of

their loved ones would not find peace in the afterlife.226

A long-held Chinese

Taoist belief was that those who suffered violent deaths and did not

receive ritual offerings of food at their graves would eventually turn

into ‘hungry ghosts’.227

Indeed,

when the monument

was unveiled in 1967,

the crowd in attendance consisted

various religious leaders from various faiths as well as the many

families of the dead, especially mothers of the deceased.228

|

|

Civilian War Memorial

The Civilian War Memorial is a

monument dedicated to civilians who perished during the Japanese

Occupation of Singapore (1942–45). It is located on a parkland, along

Beach Road, opposite Raffles City.

The memorial’s structure comprises

four tapering columns of approximately 68 m high. These columns

symbolise the merging of four streams of culture into one and the

principle of unity of all races. It resembles two pairs of chopsticks,

so it is affectionately called the “chopsticks” memorial. Since its

unveiling on 15 February 1967 (exactly 25 years after Singapore fell to

the Japanese), ex-servicemen, families and others gather at the memorial

every year on 15 February to commemorate that fateful day.

History

During World War II, Singapore fell to the Japanese forces, who occupied

Singapore from 15 February 1942 to 12 September 1945.

On 21 February 1942, the Japanese carried out a military operation aimed

at eliminating anti-Japanese elements from the Chinese community in

Singapore. The operation, which came to be known as “Sook

Ching”, lasted two weeks, during which Chinese males between 18

and 50 years old were summoned to various mass screening centres. Those

suspected of being anti-Japanese were then executed.

The number of those taken away and massacred has been an unknown.

Immediately after the war, investigation conducted in Tokyo on the Sook

Ching operation produced the figure of around 5,000, while Kempeitai

(Japanese military police) reports indicated 6,000. The Singapore

Chinese Chamber of Commerce (SCCC), on the other hand, reported a figure

of 40,000 during post-war reparation claims from the Japanese.

Discovery of human remains

On 24 February 1962, an article in The Straits Times, “Mass war graves

found in Siglap’s ‘valley of death’”, reported the discovery of five

separate war graves in Siglap. The graves contained the remains of

civilian victims massacred by the Japanese army during the Japanese

Occupation.

The human remains were first uncovered during sandwashing operations in

an area off Siglap Road. After subsequent investigations by a SCCC team

comprising Ng Aik Huan, Toh Keng Tuan and Lam Thian, five mass graves

were located. The discovery prompted the chamber to make a public call

for information on other such graves in Singapore.

Further investigations uncovered 40 more mass war graves, off Evergreen

Avenue in Siglap. Another two were found at the 10.5 milestone along

Changi Road, where Ng claimed that more than 1,000 people were

machine-gunned and buried.

Proposal for a civilians grave and monument site

On 28 February 1962, the SCCC formed a committee to undertake the

exhumation of the discovered war graves and reburial of the remains. The

chamber also asked the Singapore government for a piece of land for the

reburial and to erect a memorial, as well as to seek compensation from

the Japanese government for the massacre of civilians during the

Japanese Occupation. However, reparation could only be sought through

the British government since Singapore’s foreign affairs were still in

the hands of the British.

On 14 March 1962, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew announced in the

legislative assembly that the Singapore government had asked the British

government to seek amends and atonement from the Japanese government, in

connection with the massacre committed by the Japanese during the war.

Lee also announced that a park and

memorial would be built at Siglap for those massacred by the Japanese

during the war, if the Japanese would make compensation.

The Civilian War Memorial project

On 13 March 1963, the Singapore government announced that it would set

aside 4.5 acres (1.8 ha) of land along Beach Road, opposite Raffles

Institution, for the building of a memorial and park to commemorate the

civilian victims massacred during the Japanese Occupation. The remains

from the discovered mass graves would be cremated and the ashes placed

in the park. The cost of constructing the memorial was estimated at

$750,000. The government would pay half of the construction cost by

matching public donation on a dollar-to-dollar basis.

Days later on 19 March, the SCCC set up a Memorial Building Fund

Committee to raise funds for the construction of the memorial. A public

meeting was then convened on 21 April. Attended by more than 1,000

representatives from 509 societies in Singapore, including those from

the Malay, Indian, Ceylonese and Eurasian communities, the meeting

raised more than $100,000. Further donations received after the meeting

amounted to $30,000.

Ground-breaking ceremony

On 15 June 1963, a gathering which included representatives from the

Inter-Religious Organisation and members of the consular corps witnessed

Lee performing the ceremony of “turning (or breaking) the sod” to lay

the foundation for the memorial.

In conjunction with the ground-breaking ceremony, a one-week exhibition

was held at the Victoria Memorial Hall, which showcased 25 designs for

the memorial, received in a competition held earlier in March.

Architectural firm Swan and Maclaren won the best design, which

originally comprised a rectangular raised platform enclosing a vault in

which the ashes of victims would be placed. A total of 12 parallel sets

of concrete fins were to be built above the rectangular platform to form

a 30-metre high archway.19 However, the design had to be amended when

the original plan of cremating the remains had to be changed to

reburial, out of respect for the different religions. The design for the

memorial was thus revised to the present one, which comprises four

tapering columns. It was designed by Leong Swee Lim of Swan and

Maclaren.

Unveiling of memorial

The memorial was completed in January 1967 at a cost of approximately

$500,000.21 Before its completion, a ceremony was held on 1 November

1966, during which 606 urns

containing the remains from the mass graves were interred on either side

of the memorial podium.

The memorial was officially unveiled by Lee on 15 February 1967, which

was the 25th anniversary of the fall of Singapore. In his speech, Lee

said, “We meet not to rekindle old fires of hatred, nor to seek

settlements for blood debts. We meet to remember the men and women who

were the hapless victims of one of the fires of history. This monument

will remind those of us who were here 25 years ago, of what can happen

to people caught completely unaware and unprepared for what was in store

for them. It will help our children understand and remember, what we

have told them of this lesson we paid so bitterly to learn”.

Before Lee unveiled a plaque and laid the first wreath on behalf of the

government and the people of Singapore, prayers were said by leaders of

the Inter-Religious Council representing Muslim, Buddhist, Christian,

Hindu, Jewish, Sikh and Zoroastrian faiths. A three-minute silence

followed the laying of the wreaths. The event was attended by many

families of the dead, especially the mothers.

Description

The memorial was built on a burial chamber which houses 606 urns

containing the remains of thousands of unknown civilians exhumed by SCCC

from the discovered mass graves.

The monument’s structure comprises four tapering columns of

approximately 68 m high, representing four streams of culture merging

into one.26 Within the columns and resting on top of a pedestal is a

large bronze urn with small lion heads all-round, symbolising the

remains of the dead buried beneath.27 The base of the monument is

surrounded by a shallow pool of water, giving it an atmosphere of

serenity.

Surrounding the memorial is a parkland, which was laid out three years

after the memorial was erected.

Annual commemoration

Since the memorial was officially unveiled, commemorations, ceremonies

and services have been held there every year on 15 February to remember

civilians who were killed during the Japanese Occupation.

Total Defence Day is also marked

annually on 15 February to commemorate the fateful day in 1942 when

British forces surrendered Singapore to the Japanese.

The memorial was gazetted as a national monument on 15 August 2013.

This year in 2025

is the 58th edition -anniversary .

|

日治时期蒙难人民纪念碑,

日本占领时期死难人民纪念碑

它建于 1967 年,高 68 米,是为纪念二战时期死难的平民而建。

四根白色立柱象征着新加坡的四大种族,体现了不同种族在日占时期所共同承受的磨难。纪念碑不仅仅是为了缅怀死者,更是为了提醒世人战争的残酷及新加坡社会在战后重建中所展现的团结精神。

新加坡平民战争纪念碑是一座纪念新加坡日治时期(1942-45

年)遇难平民的纪念碑。纪念碑位于莱佛士城对面的美芝路旁的公园内。纪念碑由四根约 68 米高的锥形柱组成。

这些柱子象征着四大文化流派的融合和各族团结的原则。纪念碑的形状类似于两双筷子,因此被亲切地称为“筷子”纪念碑。

自纪念碑于 1967 年 2 月 15 日(新加坡沦陷 25

周年)揭幕以来,退役军人、家属和其他人每年都会在 2 月 15 日聚集在纪念碑前,纪念那个决定性的日子。

历史

第二次世界大战期间,新加坡沦陷于日军手中,日军于 1942 年 2 月 15 日至 1945 年 9 月 12 日占领新加坡。

1942 年 2 月 21 日,日军发动军事行动,旨在从新加坡华人社区中清除反日分子。该行动后来被称为“肃清行动”,持续了两周,期间 18 至

50 岁的华人男性被传唤到各种大规模筛查中心。那些被怀疑反日的人随后被处决。

被带走并被屠杀的人数不详。战争结束后,东京对肃清行动的调查得出的数字是约 5,000 人,而日本宪兵队 (日本宪兵队) 的报告则显示有

6,000 人。另一方面,新加坡中华总商会 (SCCC) 在战后向日本索赔时报告的数字是 40,000 人。

发现人类遗骸

1962 年 2 月 24

日,《海峡时报》刊登了一篇题为“实乞纳‘死亡之谷’发现集体战争坟墓”的文章,报道了在实乞纳发现五个独立的战争坟墓。这些坟墓里埋葬着日军占领期间被日军屠杀的平民受害者的遗骸。

这些人类遗骸首先是在实乞纳路附近地区的洗沙作业中发现的。随后,由 Ng Aik Huan、Toh Keng Tuan 和 Lam Thian

组成的 SCCC 小组进行了调查,找到了五个集体坟墓。这一发现促使该商会公开征集新加坡其他此类坟墓的信息。

进一步的调查在实乞纳常青大道附近发现了 40 多个集体战争坟墓。在樟宜路沿线 10.5 英里处发现了另外两个,Ng 声称有 1,000

多人在那里被机枪射杀并埋葬。

提议设立平民墓地和纪念碑

1962 年 2 月 28

日,新加坡中华总商会成立委员会,负责挖掘已发现的战争墓地并重新安葬遗骸。商会还要求新加坡政府划出一块土地,用于重新安葬和建立纪念碑,并要求日本政府就日治时期大屠杀平民作出赔偿。然而,赔偿只能通过英国政府,因为新加坡的外交事务仍由英国人掌控。

1962 年 3 月 14 日,时任总理李光耀在立法议会宣布,新加坡政府已要求英国政府就日本人在战争期间犯下的大屠杀向日本政府寻求补偿和补偿。

李还宣布,如果日本人愿意赔偿,将在实乞纳为战争期间被日本人屠杀的人们建造一个公园和纪念碑。

平民战争纪念碑项目

1963 年 3 月 13 日,新加坡政府宣布将在莱佛士学院对面的美芝路沿线划出 4.5 英亩(1.8

公顷)的土地,用于建造纪念碑和公园,以纪念日治时期被屠杀的平民受害者。发现的万人坑中的遗骸将被火化,骨灰将放置在公园中。纪念碑的建造成本估计为

750,000 美元。政府将以等额公众捐款的方式支付一半的建设成本。

几天后的 3 月 19 日,新加坡华人商会成立了纪念碑建设基金委员会,为纪念碑的建设筹集资金。随后,4 月 21

日召开了一次公开会议。会议吸引了来自新加坡 509 个社团的 1,000 多名代表参加,其中包括马来人、印度人、锡兰人和欧亚人,会议筹集了 10

多万美元。会议结束后,又收到了 3 万美元的捐款。

奠基仪式

1963 年 6 月 15 日,宗教间组织代表和领事团成员在场,见证了李光耀主持“翻土(或破土)”仪式,为纪念碑奠基。

奠基仪式的同时,维多利亚纪念堂还举办了为期一周的展览,展示了 3 月初举行的竞赛中收到的 25 份纪念碑设计方案。建筑公司 Swan and

Maclaren 赢得了最佳设计,最初包括一个矩形凸起平台,围绕着一个墓穴,将受害者的骨灰安放在其中。矩形平台上方共计建造了 12

组平行的混凝土翼板,以形成 30 米高的拱门。19

然而,出于对不同宗教的尊重,原计划将遗体火化改为重新埋葬,因此不得不修改设计。纪念碑的设计因此修改为现在的样子,由四根锥形柱子组成。它是由

Swan and Maclaren 的 Leong Swee Lim 设计的。

纪念碑揭幕

纪念碑于 1967 年 1 月竣工,耗资约 500,000 美元。21 竣工前,于 1966 年 11 月 1

日举行了一场仪式,在纪念台两侧安放了 606 个装有万人坑遗体的骨灰瓮。

纪念碑于 1967 年 2 月 15 日由李光耀正式揭幕,当天是新加坡沦陷 25

周年纪念日。李在演讲中说:“我们聚在一起不是为了重燃仇恨的旧火,也不是为了寻求血债的和解。我们聚在一起是为了缅怀那些在历史之火中不幸牺牲的男男女女。这座纪念碑将提醒我们这些

25

年前曾在这里的人,对于那些完全没有意识到、没有做好准备的人来说,会发生什么。它将帮助我们的孩子理解和记住我们告诉他们的这个我们付出惨痛代价才学到的教训。”

在李揭牌并代表新加坡政府和人民敬献第一个花圈之前,代表穆斯林、佛教、基督教、印度教、犹太教、锡克教和琐罗亚斯德教的宗教间理事会领导人进行了祈祷。献花圈后进行了三分钟的默哀。许多死难者家属参加了此次活动,尤其是母亲们。

描述

纪念碑建在一个墓室上,墓室里有 606 个骨灰瓮,里面装着 SCCC 从发现的集体坟墓中挖掘出的数千名无名平民的遗骸。

纪念碑的结构包括四根大约 68 米高的锥形柱子,代表四股文化潮流合二为一。26

在柱子内部,底座上放着一个巨大的青铜瓮,四周都是小狮子头,象征着埋在下面的死者的遗骸。27 纪念碑的底座被一个浅水池包围,给人一种宁静的氛围。

纪念碑周围是一片公园,是在纪念碑建成三年后规划的。

年度纪念

自纪念碑正式揭幕以来,每年 2 月 15 日都会在那里举行纪念、仪式和服务,以纪念在日本占领期间遇害的平民。

每年 2 月 15 日也被定为“全面防卫日”,以纪念 1942 年英军向日本投降新加坡的那个决定性的日子。

2013 年 8 月 15 日,该纪念碑被列为国家纪念碑。

|

|

|

|

承前启后的新月:艺术作品。

從洞里往前看和向后看是不同建筑,新和旧的对比。

新的是金沙,旧的是市政区。

|

|

海滨公园

下车点在维多利亚剧院侧面

下车带贵宾们过去可以选择从五丛树下的路进去或者丛林谋盛纪念碑那边的路进去,下面以从五丛树下五路进去

大家好,我是你们今天的导游,我叫***,大家可以叫我**,请允许我点一下人数,好的,全员到齐,现在开始我们今天主题,殖民遗产之旅的第三个景点,海滨公园

海滨公园始建于1943年,1991年进行了重修。它位于新加坡最繁华的区域之一,周边环绕的是康乐通道。这个公园每年都有不计其数的游客来访。这里有许多纪念碑和地标式建筑,如印度国民军纪念碑、阵亡纪念碑、伊丽莎白女王步道和陈金声喷泉以关闭在装修。每年,春到河畔迎新年,也就是华裔农历新年,都会在这里举行。

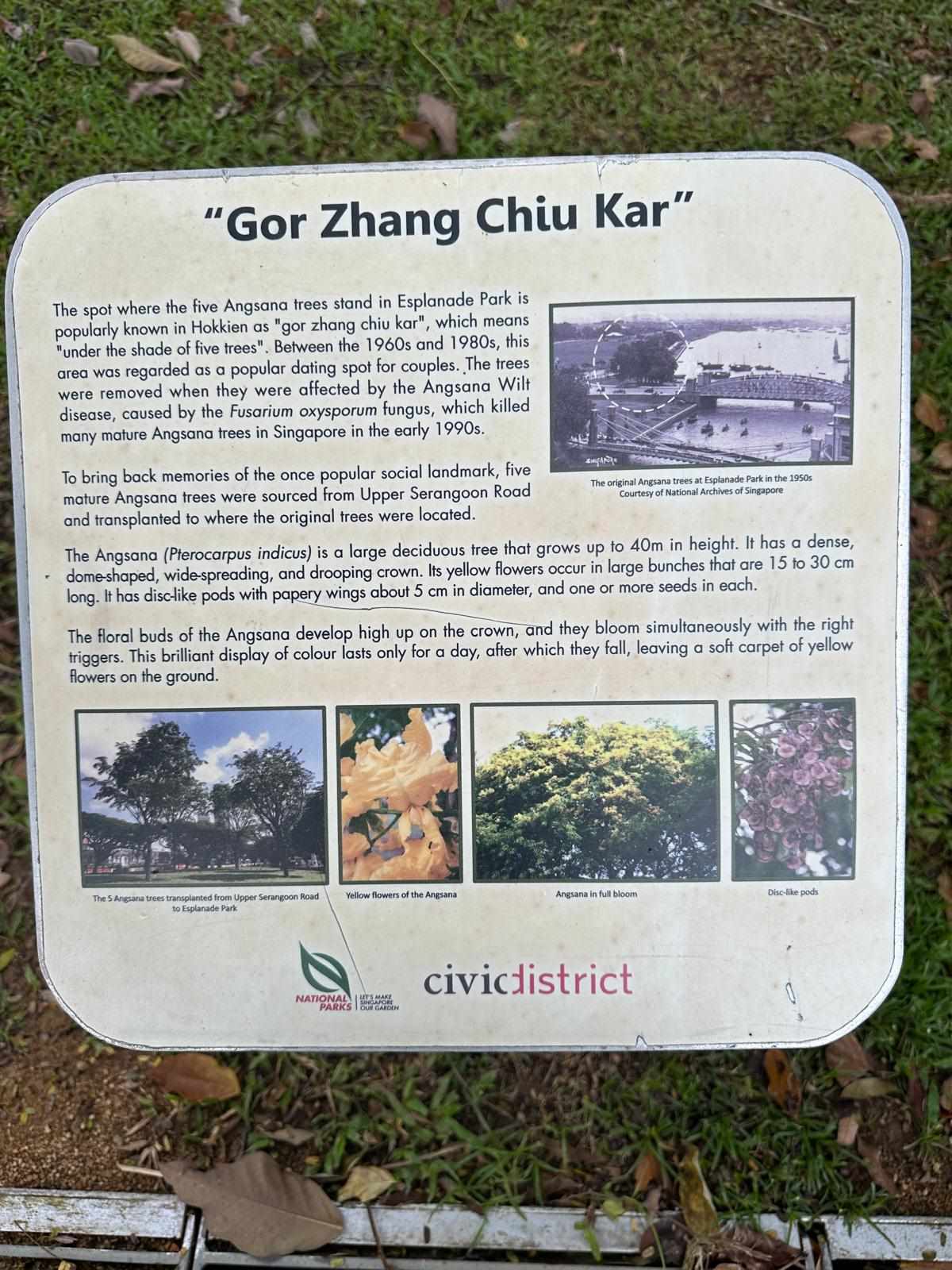

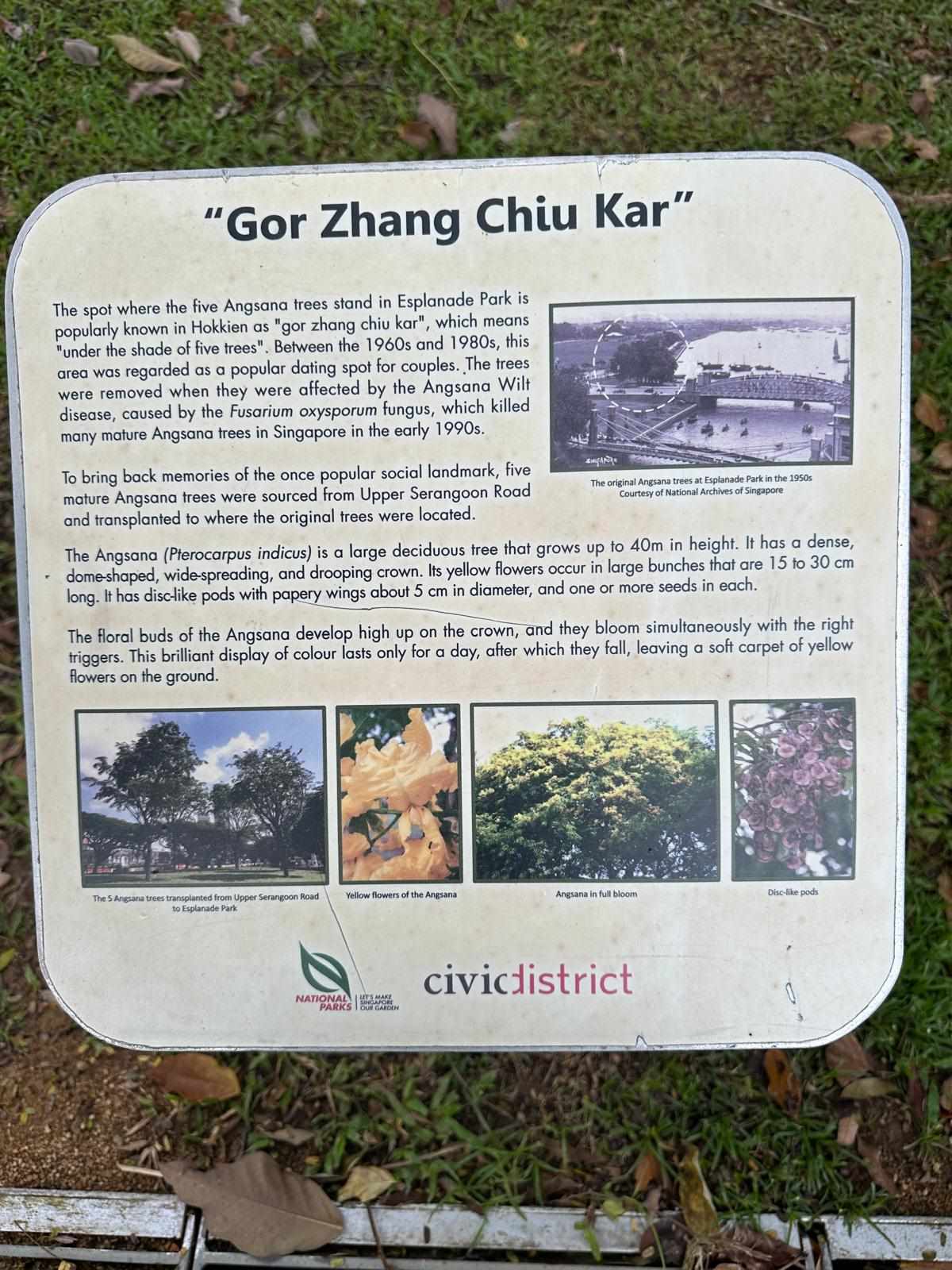

1.海滨公园的前身——五丛树脚,名称来自闽南语,是五株树下的意思。这五棵树就是青龙木。由于它是民间通俗名称,后来在50年代被新建的伊丽莎白女皇道所取代,但五丛树脚还通用于民间,那一年代不论男女老少,从一对对的情侣到拖大拉小的家庭外游,五丛树脚都是大家休闲的好去处。

20世纪80年代末至90年代初,总共有五棵成年青龙木被病菌感染,相等于一年一棵的惊人数量。为了避免病菌的大规模扩散,国家公园局只好把它们移走以杜绝后患。

所以现在大家现在看到的五丛树不是那时侯的五丛树是经过多年的努力,多名来自国家公园局的园艺学家,终于培育出一种能够抵抗病菌的青龙木新品种。值得一提的是,这五棵青龙木是从115棵成功培植的新成员里挑选出来。据报道,国家公园局花了一个月周详计划,再花上一月的时间才将这五棵茁壮的青龙木从比达达利(Bidadari)绿地移植到滨海公园。

土生土长的青龙木,在上个世纪六七十年代被大量的种植,过后又在80年代被病菌大肆侵袭,真可说是走过多少岁月的风风雨雨。

2.大家看现在河边很多人在走,跑步的这个步道,就是伊丽莎白女王步道,是一条位于滨海公园(Esplanade

park)的海滨步道(Promenade),同样为了纪念英女王1953年登基而命名。

步道在1953年5月30日由陆婉平女士宣布开放使用。

伊丽莎白女王步道是用二战后募捐来的资金填海建造的,募款主要用于修建纪念战争中阵亡的士兵纪念碑和纪念馆

在1970年代,那这条步道是曾经很多人的回忆,这边有个露天美食沙爹俱乐部,是当时很多年轻男女约会的地方,在这边也发生一些有趣故事,有个男的要约了女的来这边相亲,听说她的胃口最多两串沙爹,听了非常满意,第一次约会也真的只是两串沙爹的开销,就觉得女方是经济实惠型,好养活,结婚之后才知道,两串沙爹只是含蓄说话,可是这婚已经结了,这是因为一个误会而成就了一段佳偶。

大家移步往前

3. 林谋盛纪念碑

陆军少将林谋盛 (Lim Bo Seng)

是第二次世界大战中一位新加坡战争英雄,矗立于滨海公园的林谋盛纪念塔是为了纪念这位英雄的丰功伟绩,现在被列为国家古迹。

这位著名的福建商人在日据之前和日据期间领导了多次抗日活动,包括筹集资金支持中国的抗日战争,以及在马来西亚创建情报网。因遭叛徒出卖,他在怡保被日军秘密警察逮捕,入狱后受尽折磨。1944

年 6 月 29 日,林谋盛死于华都牙也监狱 (Batu Gajah Jail)。

中国国民政府追封林谋盛为陆军少将。

1946 年 1 月 13 日,英军将林谋盛遗体带回新加坡,并以军礼将他重新埋葬在麦里芝蓄水池,林谋盛的墓地至今保留于此。1954

年揭幕的林谋盛纪念塔由建筑师黄庆祥设计,纪念塔所在地则由政府划拨。华人社群捐款筹募建筑纪念塔所需资金。

这座 3.6

米高的八边形纪念塔由铜、水泥和大理石建成,是展现华人建筑风格的一件重要作品,也是新加坡唯一一座纪念二战个人英雄的纪念塔。这座纪念塔有三层铜制塔顶,并在塔基安放了四尊铜狮。四面铜制纪念匾用英语、中文、淡米尔语和爪夷文(马来语)记载了林谋盛的光辉一生,请花点时间细读。2010

年 12 月 28 日,林谋盛纪念塔被正式列为国家古迹,同时享此殊荣的还有世界大战阵亡战士纪念碑 和陈金声喷泉。

4. 承前启后的新月

“承前启后的新月”是新加坡滨海堤坝的一项艺术装置或理念表达,象征着新加坡在历史、现在与未来之间的连接。滨海堤坝作为新加坡重要的可持续发展项目,这一象征表达了创新与传统的交融,以及对未来的展望。

•承前:代表新加坡对过去的传承与致敬,包括向建国先驱和历史积淀的尊重。

•启后:体现了新加坡通过科技与环保措施,朝向可持续未来迈进的决心。

•新月是新加坡国旗上的标志之一,寓意国家的新生和希望,反映了一个充满活力的国家不断向前发展的精神,

新月也可以被解读为一轮满月的开始,寓意着无限的可能性和未来的光明。

滨海堤坝是一个多功能的工程设施,同时融合了生态保护与休闲功能。“承前启后的新月”这一理念完美契合滨海堤坝的设计与用途,包括以下几点:

历史的延续:作为新加坡第15个水库,滨海堤坝为水资源管理和防洪提供了创新解决方案,承接了新加坡一贯的城市发展规划精神。

未来的展望:通过可再生能源(如太阳能)和水资源管理技术,滨海堤坝展示了可持续城市生活的样板。

“承前启后的新月”通常被视为滨海堤坝上草坪观景区域的一部分,这里可以俯瞰滨海湾天际线,包括著名的滨海湾金沙、鱼尾狮公园和滨海艺术中心。

这一象征使滨海堤坝超越了工程设施的功能,成为一个代表新加坡精神的文化地标,也是游客了解新加坡过去与未来的窗口。游客在欣赏壮丽景观的同时,也能体会这一理念的深刻寓意。

5. 抗共纪念碑

纪念碑的背景和寓意

1. 背景历史:

•

纪念碑记录了新加坡人民在1948年至1989年期间与马来西亚共产党暴力和颠覆活动作斗争的历史。这一时期,也被称为“马来亚紧急状态”,新加坡和马来亚面对了共产主义的威胁。

• 共产党通过武装斗争试图颠覆政府,推翻殖民统治并建立共产主义政权。这一威胁影响了整个地区的安全与稳定。

2. 寓意:

• 纪念碑旨在铭记那些在冲突中抵抗暴力和颠覆活动的个人和团体,感谢他们为新加坡的独立、民主和非共产主义社会所付出的努力。

• 它提醒后人珍惜新加坡来之不易的和平与繁荣,并反思团结与坚韧对国家发展的重要性。

对游客的解说词

• 开场白:

“欢迎来到滨海公园的这一历史地标——‘新加坡人与马来西亚共产党暴力及颠覆活动之斗争’纪念碑。这是一座向英勇抵抗暴力的无名英雄致敬的纪念碑。”

• 重点内容:

•

“从1948年至1989年,新加坡和马来亚经历了一段紧张时期,当时马来西亚共产党发动了一系列暴力和颠覆活动,试图建立共产主义政权。这场斗争中,许多人为了保护国家的和平和稳定而英勇牺牲。”

• “纪念碑特别献给那些抵御暴力、不畏威胁,坚定地为一个民主、非共产主义的新加坡而战的人们。”

• 收尾词:

• “纪念碑不仅是历史的见证,也是对未来的警示,提醒我们珍惜当前的和平与稳定。希望大家通过参观,了解这段历史,并感受到团结与坚持的重要性。”

5. 印度国民军纪念碑

坐落于滨海公园的印度国民军纪念碑建于 1995 年,旨在纪念二战结束 50 周年,是新加坡 11 处二战遗址中的一处。

这里原是印度国民军无名烈士纪念碑遗址,但在战后遭到损毁,如今在原址建立起这座新的纪念碑。

1942 年,在日军帮助下,印度国民军在东南亚组建而成。1942 年 2

月,英军投降,日军怂恿甚至强迫战败的英属印度部队加入印度国民军一起解放印度。

印度国民军最初由莫汉·辛格上尉 (Captain Mohan Singh) 指挥,后来转交给印度独立运动者沙布哈斯·昌德拉·鲍斯 (Subhas

Chandra Bose) 负责领导。1945 年日军投降,印度国民军遭到解散。

原有的纪念碑在日军投降之前建于滨海公园 。1945 年 7 月 8 日,鲍斯在滨海公园为纪念碑奠基。碑文是印度国民军座右铭:团结、信念和牺牲。

英军当年返回新加坡后,联军东南亚区统帅蒙巴登勋爵 (Lord Mountbatten) 下令拆除原有的纪念碑。

6. 铃铛

滨海湾公园的铃铛装置是一种艺术和互动装置,通常具有象征意义和寓意。虽然具体铃铛的背景或创作理念可能需要进一步考证,但以下是一个可能的寓意和游客解说词框架:

寓意

1. 和平与和谐:铃铛通常象征着和平、和谐与连接。通过敲响铃铛,游客可以感受到与自然和环境的共鸣,表达对美好未来的祝愿。

2. 互动与反思:铃铛装置可能旨在引导游客驻足停留,与自然互动,并反思个人与环境的关系。

3. 庆祝与祈愿:敲响铃铛也可以被视为一种庆祝或祈愿的方式,将希望和祝福传播开来。

对游客的解说词

• “欢迎来到这片宁静的角落,这里的铃铛象征着和平与和谐。每一次敲响,都是对自然的致敬,对未来的祈愿。”

• “这些铃铛不仅是一件艺术装置,更是邀请游客与环境互动的媒介。您可以轻轻敲响铃铛,感受声音回荡在自然中的瞬间平静与喜悦。”

• “据说,每一个敲响的铃声都带着希望和祝福,传递到世界的每一个角落。请为您的愿望敲响铃铛,与这片美丽的滨海湾连接。”

7.

和平纪念碑/世界大战阵亡战士纪念碑

为 纪 念 第 ⼀ 次 ⼤ 战 阵 亡 的 军 ⺠ 。正 ⾯ 共 有 五 个 梯 级 , 每 ⼀ 级 代 表 第 ⼀ 次 ⼤ 战 的 每 ⼀ 年

, 一站1 9 1 4 年⾄ 1 9 1 8 年 ,二战1939年--1945年。碑 盾 刻 有 战 死 者 的 姓 名

。他们舍己为公,因为他们的牺牲我们才得到生存。 碑 柱 直 冲 云 霄 , 巍 峨 雄 伟 !

新加坡的世界大战阵亡战士纪念碑,通常被称为 战争纪念碑 (The Cenotaph),位于市区的滨海艺术中心公园 (Esplanade

Park)。这是一个重要的历史遗迹,纪念在两次世界大战中为新加坡和马来亚献出生命的士兵。

建于1922年,最初是为了纪念在第一次世界大战(1914-1918)中牺牲的士兵。

后来在第二次世界大战(1939-1945)后,纪念碑上增加了铭文,纪念在二战中阵亡的士兵。

纪念碑由英国建筑师 Denis Santry 设计,采用了新古典主义风格。

纪念碑顶部刻有铭文 “Our Glorious

Dead”,象征对战士们的崇敬与怀念。它的基座上刻有两次大战的年份和阵亡士兵的名字。纪念碑不仅是对在两次大战中牺牲士兵的致敬,还反映了当时新加坡作为英国殖民地的历史背景,它见证了新加坡从战争年代走向现代化发展的历程。

纪念碑周围环境优美,适合步行游览, 每年的重要纪念活动(如退伍军人纪念日)常在此举行。

全天开放,适合白天和晚间参观。

|

|

PADANG政府大厦大草场

大草场,马来语意为“平地”,位于市政区的显著位置。

二战期间,这里曾是欧洲人被关押并被送往樟宜监狱前的聚集地,也是二战结束后举行胜利集会的场地,同时是新加坡国庆阅兵和其他休育赛事的热门场地。

新加坡政府认识到其重要性,已将其列入联合国教科文组织名录的世界文化遗产预备名单。

The Padang in Singapore holds immense historical significance as a

venue for key events, including BRTISH pow MARCH TO CHANGI FROM THERE,

the Japanese surrender in 1945, the announcement of Singapore's merger

with Malaysia in 1963, and the first National Day Parade in 1966. It's

now also a national monument, representing Singapore's journey from

colonial rule to independence.

Here's a more detailed look at its historical importance:

Colonial Era:

The Padang was established in the 1820s as a recreational field for

cricket and other sports, marking its early role as a communal space.

It served as a venue for various events, including celebrations for

royal birthdays, jubilees, and coronations.

During the Japanese occupation in World War II, the Padang was used for

military parades.

Post-War and Independence:

In September 1945, a victory parade was held at the Padang to

commemorate Japan's formal surrender.

The Padang was the venue for the installation of Yusof Ishak as the

first Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State) in December 1959.

In 1963, it was at the Padang that founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew

announced Singapore's merger with Malaysia.

After separation from Malaysia, Singapore held its first National Day

Parade at the Padang in 1966, a tradition that continues today.

Modern Significance:

The Padang remains an important public space, used for national events

like the annual National Day Parade.

It continues to function as a key recreation and commemorative space for

members of all communities, hosting major sporting events.

On August 8, 2022, the Padang was gazetted as Singapore's 75th national

monument, recognizing its historical significance.

The Padang Civic Ensemble, including the Padang and surrounding

buildings, has been placed on Singapore's tentative list of Unesco World

Heritage Sites.

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

![]()

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)