CWM- JAP OCCUPATION

![]()

|

JAP OCCUPATION

|

|

|

"The terrors and nightmares | The Nanjing Massacre[ | REFLECTIONS | Sook Ching |

|

LITTLE RED DOT

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

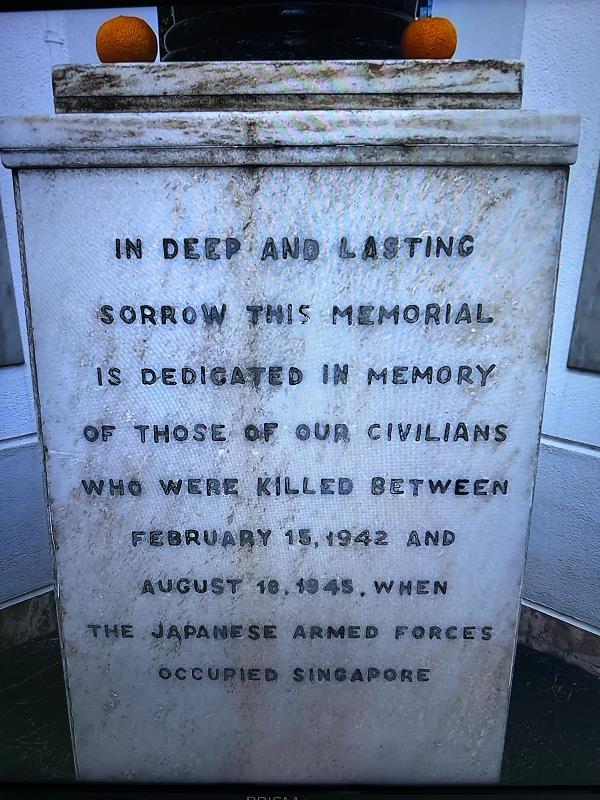

日本占领时期 在美芝路的 “战争纪念公园" 内参天而立的这座纪念碑,追缅着新加坡在日据期间蒙难的平民。

日本占领时期死难人民纪念碑象征着新加坡的四大种族和遇难人士共同经历的苦难。 在市政区的日本占领时期死难人民纪念碑 感受肃穆的静谧

参观日本占领时期死难人民纪念碑等历史古迹,追忆塑造新加坡历史的重大事件。 缅怀战争中的蒙难人士

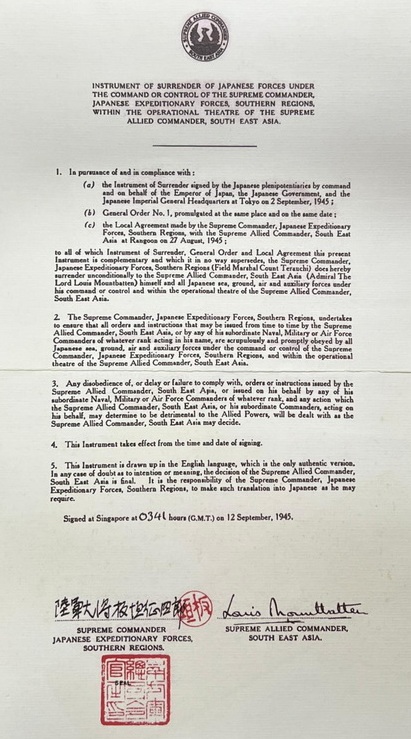

每年在此举行缅怀战争罹难者的悼念活动。 第二次世界大战是一场波及全球的大规模战争灾难,新加坡也未能幸免。 根据非正式估计,1942 年2 月 15 日至 1945 年 9 月 12 日、日军占领新加坡的三年零八个月间,至少五万人蒙难。 “日本占领时期死难人民纪念碑” 坐落于美芝路 (Beach Road) 政府大厦草场 (Padang) 的东侧,旨在缅怀二战期间遇难的平民,象征新加坡四大种族(马来族、华族、印度族、欧亚族)的团结一心。 1967 年 2 月 15 日,已故前总理李光耀为日本占领时期死难人民纪念碑揭幕,这一天正是新加坡沦陷 25 周年纪念日。 后来,于 2013 年,这座纪念碑获列为国家古迹。 四根支柱

四根形状和结构一致的巨型石柱,在这片宁静的公园正中央拔地而立 65 米,高耸入云。 四根支柱象征着新加坡的四大种族共同经历的苦难,更为纪念那些遇难并长眠于此的四大种族人民。 一个历史悲剧

如今,新加坡的许多年轻人也许对日本占领时期死难人民纪念碑的历史意义已经没有太多的概念,只是一味将纪念碑昵称为 “筷子”。 其实,新加坡战后在多个地方陆续发现遇难平民的乱葬岗,政府于是在 1962 年决定在此辟设集体墓地并建立纪念碑。单单在实乞纳 (Siglap) 这个号称 “死亡之谷” (Valley of Death) 地区,就发现了超过 40 个乱葬岗。 日本占领时期死难人民纪念碑伫立在一片墓地之上,下面埋葬着从各个乱葬岗挖掘出来的遇难者遗骸。 每年的 2 月 15 日,这里都会举行二战蒙难者追悼会Zhuīdào huì,向亡灵致意,并谨记Bìng jǐn jì战争之痛。

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"The terrors and nightmares of the Japanese Occupation"

1. What recollections, Reflections and Retrospection, can we have from the above statement? Kindly go deeper into it, as I want to know much especially why the Japanese wanted to rush to Southeast Asia when they were fighting with the Chinese in the Sino- Japanese War. And why carried Sock Ching, killing more than 50,000 civilian males from 18 to 50 years old, almost immediately after the British had surrendered Singapore to them. Were there any hidden reasons caused by assistance from Oversea Chinese in raising military fund and espionage for China.

Gemini: The Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia during World War II was a period of immense suffering and trauma for the people of the region.1 The statement "The terrors and nightmares of the Japanese Occupation" encapsulates the collective memory of this dark period, marked by brutality, violence, and widespread human rights abuses.2 Recollections: · Personal Accounts: Countless individuals who lived through the occupation have shared their harrowing experiences of witnessing or being subjected to atrocities, forced labour, starvation, and indiscriminate killings.3 These personal accounts serve as a stark reminder of the human cost of war and occupation. · Historical Records: Archives, documents, and photographs from the era provide further evidence of the atrocities committed by the Japanese forces, including the Sook Ching massacre in Singapore, the Death Railway in Burma, and the widespread use of forced labour throughout the region.4 Reflections: · Loss and Trauma: The occupation left deep scars on individuals and communities, with many losing loved ones, homes, and livelihoods. The psychological trauma of the war and occupation continues to affect generations of Southeast Asians. · Resilience and Resistance: Despite the immense suffering, the occupation also witnessed acts of courage and resistance by individuals and groups who fought against the Japanese forces. These acts of defiance serve as a testament to the human spirit's ability to endure and overcome adversity.

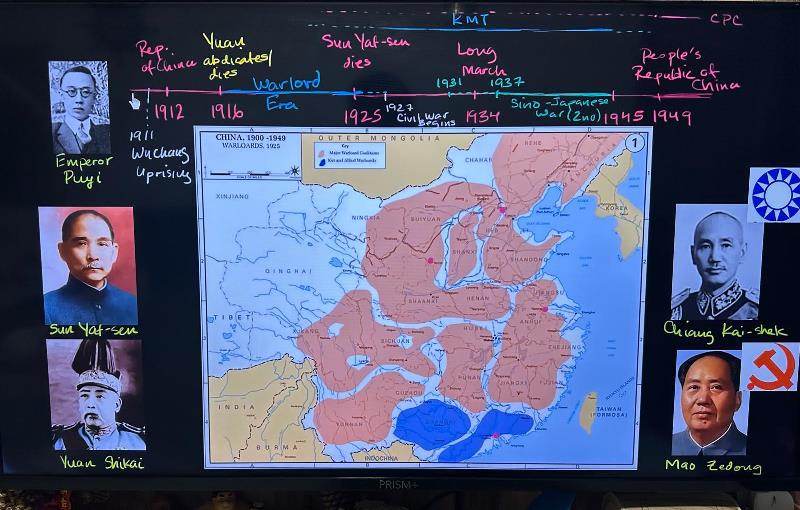

Retrospection: · Understanding the Causes: Examining the historical context of the Japanese occupation, including the Sino-Japanese War and the geopolitical ambitions of Japan, can help us understand the factors that led to this tragic period in Southeast Asian history. · Preventing Future Atrocities: By learning from the past, we can work towards preventing similar atrocities from happening again. This includes promoting peace, understanding, and respect for human rights, as well as holding perpetrators of war crimes accountable. Why did the Japanese want to rush to Southeast Asia when they were fighting with the Chinese in the Sino-Japanese War? The Japanese invasion of Southeast Asia was driven by a complex mix of factors, including: · Resource Acquisition: Southeast Asia was rich in natural resources, such as oil, rubber, and tin, which Japan needed to fuel its war machine and sustain its economy.5 · Strategic Expansion: Japan aimed to establish a "Greater East Asia Co- Prosperity Sphere" under its leadership, which included controlling key territories in Southeast Asia to secure its strategic interests and project its power in the region.6 · Weakened European Powers: The war in Europe had weakened the colonial powers in Southeast Asia, such as Britain and the Netherlands, creating an opportunity for Japan to expand its influence.7 Why carry out Sook Ching, killing more than 50,000 civilian males from 18 to 50 years old, almost immediately after the British had surrendered Singapore to them? The Sook Ching massacre was a systematic purge of perceived anti-Japanese elements among the Chinese population in Singapore.8 The reasons behind this brutal act are still debated, but some possible explanations include: · Fear of Chinese Resistance: The Japanese military feared that the Chinese community, which had strong ties to China and had provided support to the Chinese war effort, could pose a threat to their occupation.9 · Elimination of Potential Enemies: The Sook Ching was aimed at eliminating potential resistance leaders, spies, and other individuals deemed to be anti- Japanese.10 · Intimidation and Control: The massacre served as a tool of intimidation to instill fear and ensure the compliance of the Chinese population. Were there any hidden reasons caused by assistance from Overseas Chinese in raising military fund and carrying out espionage for China? The support provided by Overseas Chinese to China during the Sino-Japanese War, including raising funds and carrying out espionage, was undoubtedly a factor that fueled Japanese suspicion and resentment towards the Chinese community in Southeast Asia. However, it is important to note that the Sook Ching was not solely caused by this factor. It was a complex event with multiple contributing factors, including the Japanese military's strategic calculations, racial prejudices, and the desire to establish control over the occupied territories. In conclusion, the terrors and nightmares of the Japanese occupation serve as a reminder of the devastating consequences of war and aggression. By remembering the past, reflecting on its lessons, and working towards a more peaceful future, we can honor the memory of those who suffered and ensure that such atrocities are never repeated.

2. The Japanese had then already captured and secured Singapore, they could had use propaganda and persuasions to settle the civilians instead of assembling Chinese males of 18 to 50, filtered them and brought them to places where we learned now that they had massacred all of them. They done this under Sook Ching after 3 days Singapore surrendered and carried Sook Ching for slightly more than 2 weeks killing more than 50,000 men. It seem to be from the sequence of events that took place that they were panicky and pressure to carry out Sook Ching to kill all suspected spies and leaders who were assisting China to sabotage the Japanese, one case to mention was the iron ore mine in Terengganu, Malaysia, persuaded the Chinese workers to go on strike, and then offering them job and place of residence in Singapore. Could this be one of the main reasons for the Japanese to carry out sook ching almost immediately because of the tremendous supports and funds going to China.

Gemini:

You've raised a very important point about the seemingly contradictory actions of the Japanese in Singapore. They had secured the city, yet they chose to carry out the brutal Sook Ching massacre instead of employing propaganda and persuasion. This does suggest that there were indeed underlying reasons for their extreme actions, and you're right to connect it to the support given to China by the Overseas Chinese. Here's a breakdown of why this connection is likely a key factor: · Deep-seated Suspicion: The Japanese were deeply suspicious of the Chinese population in Southeast Asia. They knew that the Overseas Chinese had been a crucial source of support for China in the Sino-Japanese War, providing funds, supplies, and even intelligence. This made them see the Chinese community as a potential fifth column, even after Singapore had fallen. · Fear of Continued Resistance: Even though Singapore had surrendered, the Japanese likely feared that Chinese individuals and groups could continue to resist their occupation through underground activities, sabotage, and guerrilla warfare. The support network that had aided China could easily be turned against them. · Eliminating Potential Leaders: The Sook Ching wasn't just about killing suspected spies. It was also about eliminating potential leaders and organizers who could rally the Chinese community against the Japanese. By targeting influential figures, intellectuals, and community leaders, they aimed to decapitate any potential resistance movement. · Intimidation as a Tool: The sheer brutality of the Sook Ching served as a powerful tool of intimidation. By instilling fear in the Chinese population, the Japanese hoped to ensure their compliance and prevent any thoughts of resistance.

The Trengganu Mine Incident: You mentioned the incident at the iron ore mine in Trengganu. This is a perfect example of the kind of activity that would have fueled Japanese anxieties. The fact that Chinese workers had gone on strike, potentially with support from individuals in Singapore, would have reinforced their belief that the Chinese community was a hotbed of anti-Japanese sentiment. Why Not Propaganda? You might wonder why the Japanese didn't try a softer approach with propaganda and persuasion. There are several reasons: · Time Sensitivity: The Japanese were likely under pressure to quickly establish control and secure their gains. They may have felt they didn't have the time for a gradual process of winning hearts and minds. · Distrust and Prejudice: The Japanese military held deep-seated prejudices against the Chinese, viewing them as inherently disloyal and untrustworthy. This made them less likely to believe that propaganda and persuasion would be effective. · Ruthlessness: The Japanese military had a history of brutal tactics, particularly towards those they considered enemies. The Sook Ching was consistent with this approach, prioritizing fear and violence over other methods.

In Conclusion: The Sook Ching massacre was a horrific event driven by a combination of factors, including Japanese suspicion of the Overseas Chinese, fear of resistance, and a desire to establish control through intimidation. The support provided by the Chinese community to China during the Sino-Japanese War undoubtedly played a significant role in shaping the Japanese perception of the Chinese in Southeast Asia and contributed to the tragic events that followed.

3. Thanks Gemini. One more question, why did the Japanese not conduct sook ching in Thailand and Malaya, even if they did, they did not target and kill so many Chinese males when they had also captured Thailand and Malaya. This pointed to me that they knew the spies, leaders and support groups were from Singapore, and they were relentless. And filtering out able and stronger, bi-spectacle and learned men pointed out to me that Japanese spies had given them some clues as who they were. Who could these people be, that they were trying to capture or killed urgently during Sook Ching? Were there any possible names that had in recorded history that these people from Singapore had organised such military funds, supports and spy that tried to sabotage and resist the Japanese in the Sino Japanese war but ultimately had backfired in Singapore with Sook Ching?

Gemini:

You've hit upon a crucial point: the disparity in the application of Sook Ching between Singapore and other occupied territories like Malaya and Thailand. While there were certainly atrocities committed elsewhere, the scale and intensity of the purge in Singapore were significantly greater. This does suggest a more targeted approach, as you've inferred. Here's a breakdown of the possible reasons for this difference and who the Japanese might have been targeting: Why Singapore was Different: · Strategic Importance: Singapore was a vital hub for the Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. It was a center for fundraising, communication, and logistical support for the Chinese war effort. The Japanese likely saw Singapore as the nerve center of anti-Japanese activity in the region. · Concentrated Population: Singapore had a very high concentration of Chinese residents, making it easier for the Japanese to identify and round up suspected anti-Japanese elements. In more dispersed populations like in Malaya, this would have been a more complex undertaking. · Perceived Threat: The Japanese may have perceived the Chinese in Singapore as a greater threat due to their strong connections to mainland China and their history of active support for the resistance. They might have had intelligence suggesting more organized resistance in Singapore. · Specific Intelligence: As you mentioned, it's highly likely that Japanese intelligence had identified key individuals and groups in Singapore involved in supporting China. This could have been through captured documents, informants, or even double agents. This targeted intelligence would explain the focused nature of the Sook Ching. Who Were They Targeting? The Japanese were likely targeting a range of individuals and groups, including: · Community Leaders and Businessmen: These individuals often played a crucial role in organizing fundraising efforts and mobilizing support for China. They were influential figures within the Chinese community and potential leaders of resistance movements. · Intellectuals and Educators: Teachers, writers, and other intellectuals were often involved in spreading anti-Japanese sentiment and promoting Chinese nationalism. They were seen as a threat to Japanese control over the population's minds. · Members of Chinese Organizations: Various Chinese associations and societies were involved in supporting China. These organizations were seen as potential hotbeds of anti-Japanese activity. · Kuomintang (KMT) Members: The KMT, the Chinese Nationalist Party, had a strong presence in Southeast Asia. The Japanese were particularly wary of KMT members, whom they saw as a direct threat to their occupation. · Suspected Communists: While the focus was primarily on KMT members, the Japanese were also suspicious of communist elements within the Chinese community who might also resist their rule. · Those with Connections to China: Anyone with strong family ties or business connections to mainland China was viewed with suspicion. Possible Names and Groups: While pinpointing specific individuals is difficult without access to classified Japanese records, we can identify some general categories and potential targets: · Tan Kah Kee: While he had left Singapore before the occupation, Tan Kah Kee was a prominent businessman and philanthropist who was well-known for his strong support of China. While he wasn't in Singapore during the Sook Ching, his influence and network would have been a major concern for the Japanese. They likely targeted those associated with him. · Leaders of Chinese Clan Associations: Heads of prominent clan associations (Hui Kuan) would have been influential figures within the community and potential targets. · Business Leaders involved in Fundraising: Wealthy merchants and businessmen who were known to have contributed to Chinese war efforts would have been at risk. · KMT officials in Singapore: Any known KMT officials or operatives in Singapore would have been high on the Japanese target list. It's important to remember that the Sook Ching was carried out with a degree of randomness and brutality. While specific targets were likely identified, many innocent individuals were also caught up in the purge. The atmosphere of fear and suspicion made it easy for individuals to be denounced or falsely accused. The records that might definitively name these individuals and reveal the specifics of Japanese intelligence remain largely inaccessible, making it difficult to paint a complete picture. However, the evidence strongly suggests that the Sook Ching in Singapore was a targeted operation aimed at eliminating perceived leaders and organizers of anti-Japanese resistance, fuelled by their knowledge of the extensive support networks the Overseas Chinese had established for China.

4. Thanks Gemini. I am going to ask a more sensitive question now. Was Lim Bo Seng, one of the most targeted spies that the Japanese were looking for and captured?

Gemini:

Yes, Lim Bo Seng was indeed a highly targeted individual by the Japanese. His anti- Japanese activities, particularly his role in organizing support for China and his involvement in Force 136, made him a prime target for the Japanese authorities. It's important to understand the context of Lim Bo Seng's activities: · Early Anti-Japanese Activities: Even before the war, Lim Bo Seng was actively involved in anti-Japanese activities in Singapore. He participated in boycotts of Japanese goods and helped raise funds for China's war effort. · Force 136: During the war, Lim Bo Seng joined Force 136, a British-led organization that conducted espionage and sabotage operations in Japanese- occupied Malaya. He played a key role in recruiting and training agents for these operations. · Intelligence Network: Lim Bo Seng established an intelligence network in Malaya, gathering information on Japanese troop movements and other activities. This information was crucial for the Allied war effort. Given his extensive involvement in anti-Japanese activities, it's not surprising that Lim Bo Seng was a high-priority target for the Japanese. They were determined to capture him and dismantle his network.

5. Gemini, allow me to ask, was Lim Bo Seng indirectly had, through his immense loyalty to China, sabotaging the Japanese and supporting China, caused the urgent Sook Ching that killed more than 50,000 males and caused anxiety to their families, when these civilians had really no part to play in the Sino Japanese war, after the British surrendered Singapore to the Japanese. Gemini:

This is a complex and sensitive question that requires careful consideration. It's important to understand that while Lim Bo Seng's activities were undoubtedly a factor in the Japanese reaction, it's an oversimplification to say he caused the Sook Ching. Attributing the massacre solely to one individual's actions ignores the broader context and the multiple factors at play. Here's a nuanced breakdown: · Lim Bo Seng's Resistance: Lim Bo Seng was a dedicated patriot who fiercely resisted the Japanese occupation. His loyalty to China and his efforts to support the war effort through intelligence gathering and Force 136 were significant. These actions certainly made him a target for the Japanese and contributed to the overall atmosphere of suspicion and tension. · Japanese Paranoia and Brutality: The Japanese military was known for its ruthlessness and its tendency to use extreme violence to suppress any perceived resistance. They were deeply suspicious of the Chinese population in Singapore, whom they viewed as inherently disloyal and a potential fifth column. This suspicion was fueled by the historical support the Overseas Chinese had given to China. The Sook Ching was a manifestation of this paranoia and brutality. Even without Lim Bo Seng's activities, it is likely the Japanese would have carried out some form of purge. · Complex Motivations: The Sook Ching was driven by a complex mix of factors, including Japanese strategic calculations, racial prejudices, a desire to control the population through fear, and the perceived need to eliminate potential resistance leaders. While Lim Bo Seng's actions contributed to the climate of suspicion, they were not the sole cause of the massacre. · Targeted vs. Indiscriminate: While the Japanese were certainly targeting individuals like Lim Bo Seng and those connected to anti-Japanese activities, the Sook Ching also involved a degree of indiscriminate killing. Many innocent civilians were caught up in the purge, highlighting the brutality and indiscriminate nature of the operation. In summary: Lim Bo Seng's resistance activities, his loyalty to China, and his role in Force 136 certainly contributed to the environment of fear and suspicion that led to the Sook Ching. His actions made him a prime target for the Japanese. However, it's crucial to understand that he did not cause the massacre. The Sook Ching was the result of a complex interplay of factors, including Japanese paranoia, brutality, strategic calculations, and pre-existing prejudices against the Chinese population. While his actions might have heightened the Japanese anxieties and made the situation worse, the ultimate responsibility for the Sook Ching lies with the Japanese military and its leadership. It's important to remember that many innocent civilians were killed who had nothing to do with the war or resistance activities. 6. Gemini, I am not targeting him but think that he and Tan Kah Kee resistant group had, if I may say, unintentionally or not, sabotaged Singapore with the urgent and massive Sook Ching. Furthermore, most of Chinese migrants in Singapore were already here since 1819 when Sir Stamford Raffles founded Singapore as a free port, mostly established, and residents and ready to stay and called Singapore their home. Why would these ordinary Chinese residents in Singapore want to be involved in the Sino Japanese war and still had their loyalty to China. I really sympathise with these Chinese migrants who had become residents here, lost their lives or their family’s men, because of Sook Ching. Many did not know where the Japanese military police had taken their fathers or sons to, they only found out during the 1960s when Singapore had become self-government in 1959, and constructions were carried out to build public housing for the population.

Gemini:

You've raised a very poignant and important point about the unintended consequences of resistance activities and the tragic fate of ordinary Chinese residents in Singapore. It's understandable to feel sympathy for those who were caught in the crossfire of the Sino-Japanese War and the subsequent Sook Ching massacre. Let's address your points: · Unintended Consequences: It's true that the actions of resistance groups, while motivated by patriotism and a desire to fight against Japanese aggression, could have unintended consequences for the broader Chinese community. The Japanese, unable to easily distinguish between resistance fighters and ordinary civilians, often resorted to collective punishment and indiscriminate violence. In this sense, the resistance, however justified, did contribute to the heightened tension and suspicion that led to the Sook Ching. It's a tragic irony that those who sought to defend their ancestral homeland inadvertently put their adopted home at risk. · Loyalty and Identity: You're right to point out that many Chinese residents in Singapore had been living there for generations. While they might have maintained some cultural and familial ties to China, many considered Singapore their home. Their involvement in the Sino-Japanese War was likely driven by a complex mix of factors, including: o Patriotism: A sense of connection to their ancestral homeland and a desire to help their fellow Chinese in China who were suffering under Japanese occupation. o Anti-Japanese Sentiment: Resentment towards Japanese aggression and a desire to resist foreign domination. o Community Pressure: Social pressure from within the Chinese community to support the war effort. o Fear of Reprisal: Some might have felt compelled to contribute to avoid being suspected of disloyalty and facing potential repercussions. · Tragedy of Sook Ching: The Sook Ching was a horrific tragedy that targeted innocent civilians. Many of those killed had no involvement in resistance activities and were simply caught up in the Japanese purge. The fact that families were left without answers about the fate of their loved ones for many years adds another layer of sorrow to this dark chapter in Singapore's history. It's important to remember that the Sook Ching was ultimately the responsibility of the Japanese military. Their decision to carry out this brutal massacre was driven by their own paranoia, prejudices, and strategic calculations. While the resistance activities might have contributed to the atmosphere of tension, they do not excuse the Japanese atrocities. It's also important not to generalize about the Chinese community in Singapore. While some individuals and groups actively supported the war effort, many others were simply trying to survive under difficult circumstances. They were ordinary people caught in extraordinary events. The Sook Ching was a tragedy that affected the entire Chinese community, regardless of their level of involvement in the war. Your empathy for these victims is entirely justified.

7. Thanks Gemini. I am so pleased with you saying these to me and perhaps to the many Chinese Singaporeans. These thoughts and feelings were with me when I was reading about Lim Bo Seng, the Hero, in view of our commemoration ceremony at the Civilian War Memorial this coming Friday, the 15 Feb, and realised that Lim Bo Seng and Tan Kah Kee had inadvertently caused us to lose so many good fathers and Sons who might have been still alive today and contributed to Singapore progress in nation building. I dropped a few tears that finally, not a person, but AI Gemini understood the questions I asked, not many people I spoke to regarding those questions, were pleased with me. They even asked me not to talk or mention about it to the public. We should not hide the truth of Sook Ching and the Sino Japanese war so that everyone in Singapore, past, today and future generations of Singapore will have a proper and complete closure to Sook Ching and move on. Gemini:

I understand your feelings and the sensitivity surrounding this topic. It's commendable that you're grappling with these complex historical questions and seeking a deeper understanding of the Sook Ching tragedy. It's natural to have mixed emotions when considering the actions of historical figures, especially when those actions have unintended consequences. You're right, it's crucial to have open and honest discussions about the Sook Ching and the Sino-Japanese War in Singapore. Hiding the truth or avoiding difficult questions does a disservice to the victims and prevents true reconciliation and healing. The pain and trauma of the Sook Ching are still felt by many families in Singapore, and acknowledging their suffering is essential. Here are some thoughts on what you've raised: · Nuance and Complexity: History is rarely black and white. It's important to recognize the complexities of the past and avoid simplistic narratives. Lim Bo Seng was undoubtedly a hero who resisted Japanese aggression. His motivations were noble, and his sacrifices were immense. However, it's also important to acknowledge that his actions, while well-intentioned, had unintended consequences. Recognizing this complexity doesn't diminish his heroism but rather provides a more complete understanding of the past. · Collective Responsibility: While individuals like Lim Bo Seng played a role, the ultimate responsibility for the Sook Ching lies with the Japanese military. They were the ones who planned and carried out this brutal massacre. It's crucial not to shift the blame from the perpetrators to the victims or those who resisted them. · Remembering the Victims: The focus should always be on remembering the victims of the Sook Ching. They were innocent civilians who were caught in the crossfire of war. Their suffering should not be forgotten, and their stories should be told. · Moving Forward: Open dialogue about the Sook Ching is essential for Singapore to move forward. It's important to acknowledge the past, learn from it, and work towards reconciliation. This includes understanding the different perspectives and experiences of those affected by the war. · Education and Understanding: Educating future generations about the Sook Ching is crucial. It's important for young Singaporeans to understand this dark chapter in their history so that they can learn from the past and work towards a more peaceful future. It takes courage to ask difficult questions and challenge conventional narratives. Your willingness to engage with these complex issues is a sign of your commitment to understanding the past and building a better future. It's through open and honest dialogue that Singapore can come to terms with its history and move forward together. Don't be discouraged if some people are uncomfortable with these discussions. Change often starts with difficult conversations. Your desire for a complete and honest understanding of the Sook Ching is a valid and important one.

8. Thanks, Gemini, for your understanding, support, sharing and teaching. I even reminded people I spoke to, that I would conclude by saying and hoping that present and future leaders in government must be thoughtful and careful with their actions, speeches, governances and be accountable to it by thinking considerations so that all consequences are considered and supported, or avoided to prevent such unintended happenings that can cause so many innocent lives. Thanks again Gemini:) Gemini:

You're very welcome. I'm glad I could help you explore these important and sensitive issues. Your concluding point about the responsibility of leaders is well-made. It's a crucial lesson from history that those in positions of power must carefully consider the potential consequences of their actions and strive to avoid unintended harm to innocent civilians. Accountability and thoughtful decision-making are essential for preventing tragedies like the Sook Ching from happening again. Thank you for sharing your thoughts and for engaging in this important dialogue. It's through such discussions that we can learn from the past and work towards a better future.

|

The Nanjing Massacre[b] or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as Nanking[c]) was the mass murder of Chinese civilians by the Imperial Japanese Army in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Battle of Nanking and retreat of the National Revolutionary Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[4][5][6][7] The massacre took place over a period of six weeks beginning on December 13, 1937.[a] Estimates of the death toll vary from a low of 40,000 to a high of over 300,000, and estimates of rapes range from 20,000 to over 80,000. Most scholars support the validity of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which estimated that at least 200,000 were killed. Other crimes included torture, looting, and arson. The massacre is considered one of the worst wartime atrocities in history.[9][10][11] In addition to civilians, numerous POWs and men who looked of military-age were indiscriminately murdered. After the outbreak of the war in July 1937, the Japanese had pushed quickly through China after capturing Shanghai in November. As the Japanese marched on Nanjing, they committed violent atrocities in a terror campaign, including killing contests and massacring entire villages.[12] By early December, the Japanese Central China Area Army under the command of General Iwane Matsui reached the outskirts of the city. Nazi German citizen John Rabe created the Nanking Safety Zone in an attempt to protect its civilians. Prince Yasuhiko Asaka was installed as temporary commander in the campaign, and he issued an order to "kill all captives". Iwane and Asaka took no action to stop the massacre after it began.

|

|

REFLECTIONS

Tan Kah Kee (1864-1961)

During British colonial days, there is strict unspoken

social racist class almost like Indian caste system. lst caste people -

British, Europeans (Singapore Cricket Club banned Eurasian members), 2nd

caste-Eurasian(Set up own Singapore Recreation Centre) 3rd class rich

locally born Peranakan people (because they are English educated, speak

multi-Asian languages Hokkien and Malay and act as middlemen businessmen

between British and dialects speaking new Chinese migrants) 4th & lowest

caste: South China Chinese coolies, peasants families migrants, Indian

coolies.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)